The Story of an Old Louisiana Chapel, and it's significance to Catholic Florida.

- Roland Flores

- Aug 25, 2025

- 12 min read

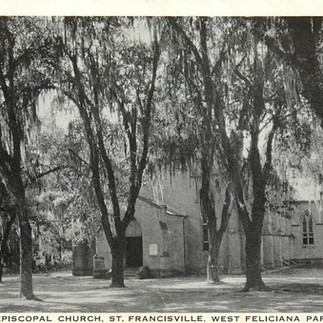

Ave María! May the Immaculate Heart of Mary be our refuge! This article is the first part of a five part series on the relations between the United States and Catholic Florida. This Prelude to our series begins in Louisiana, and our conversation begins with a protestant chapel. To make matters even more unusual, I originally learned this story and its Florida connection researching the origins of my state flag, the Texas Lonestar. Our conversation begins with the Louisiana chapel in discussion , a Protestant Chapel called “Grace Church Of West Feliciana” located in St. Francisville, Louisiana. The historic Episcopalian Church and cemetery, according to the State of Louisiana, finds its origins in 1827 as one of Louisiana’s oldest Protestant congregations. Over the following decades, this Episcopalian congregation would develop into a notable Church. During the Civil War "Grace Church" would be fired upon by Union artillery because it was the tallest structure in St. Francisville, according to the Church's own public history. "Grace Church" was later restored from the bombardment in the 1880s. If you go to the St. Francisville website and look at their historic sites listings, “Grace Episcopal Church” is the first attraction. Second is the Old Benevolent Society Building, and third is the Historic Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, a chapel built in 1871 and consecrated the Most Reverend N.J. Perche, Archbishop of New Orleans. Which is all very confusing, why would a town named after St. Francis in Louisiana (Once part of France) have an older protestant Church than the Catholic one? Why would the oldest Catholic Church not be named St. Francis? The Answers to these questions are found in the history of the town.

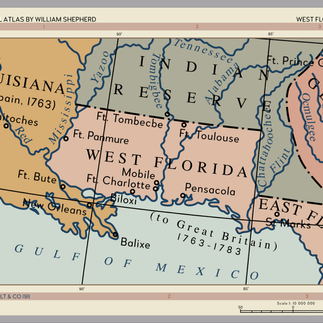

We begin in 1738 when Louisiana was a possession of the kingdom of France and Capuchin Father, Fray Anselm de Langres, established a parish Church in Pointe Coupee on the Mississippi River. At the time Louisiana was under the Bishop of Quebec, who granted ecclesiastical jurisdiction over Parish settlements to the Capuchins, including St. Louis in New Orleans and Notre Dame in Mobile. Father Anselm would dedicate this parish at Pointe Coupee to St. Francis of Assisi, whose rule the Capuchins followed. However building a cemetery in Pointe Coupee was impossible because the Missispie's annual flooding. So the Capuchins established a cemetery, and likely a chapel, on the higher bluffs, above Bayou Sara. This cemetery and chapel carried the same patronage as its parish Church, St. Francis of Assisi. After the French and Indian War, this area and all lands west of the Mississippi river, became a possession of the British empire in 1763. France's ally Spain was given everything West of the Mississippi river and New Orleans as part of the same treaty. The British made the area between the Mississippi river and Apalachicola River into the colony of West Florida, with its capital in Pensacola. The French Capuchins were likely recalled to Quebec or expelled under British penal laws, while Spanish Capuchins replaced the French friars in New Orleans in 1774. During the British occupation of the area, the red coats built Fort Richmond in Baton Rouge and the whole of West Florida, like East Florida, became a refuge for loyalist refugees from the 13 colonies. British rule did not last long, as in 1779 Spanish forces claimed the area when they captured the British positions in Baton Rouge and Natchez. Spanish rule in West Florida became official with the capture of Pensacola and surrender of the British Governor to Spanish in 1781. After the Second Treaty of Paris 1883, which solidified Louisiana and Florida as possessions of Spain, king Charles III gave a land grant to Spanish Capuchins giving them all that belonged to their French brethren before. These Spanish Capuchins built a monastery at the site of the St. Francis chapel and cemetery on the higher bluffs. A settlement sprang up around this monastery and it was called La Villa de San Francisco (St. Francis Village). Thus the city in discussion was born (or at least its foundations).

At first the young United States was friendly with its Spanish Neighbors, but soon tensions arose due to the young Republic's covetous eyes. By 1795 plans were being made to invade Spanish territory and this tension was made worse when Spain returned Louisiana to France in March 1801 as part of the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso. By this time the French revolution had occurred and France was under Napoleon Bonapart's regime. Napoleon had grand plans for North America and sent a detachment of troops to first put down a slave rebellion in Haiti and then to settle Louisiana. However, this detachment was defeated by the rebels in Haiti, and Napoleon began to realize the cost of settling Louisiana. War was on the Horizant and France desperately needed more funds. Ironically, during the time of the king just before The revolution, the revenue of the government was only supported by 30% of tax, but during the time of Napoleon that revenue was raised to 60%. With these problems, Napoleon found a solution in selling Louisiana to the United States. Not only would France receive a lump sum, but also a revolutionary ally against Great Britain and the monarchies of Europe. Napoleon wrote of this action: “I have just given To England a maritime rival that sooner or later will humble her pride." This US acquisition of Louisiana put St. Francisville into turmoil.

St. Francisville was part of West Florida, not Louisiana, and there was no official conflict in this claim as back in 1795 Spain and the US had agreed upon borders. However many did not agree with this and the area saw an influx of US Settlers, who claimed that parts of West Florida and east Texas were part of the Purchase. The claim stemmed from the fact that the original French Louisiana colony encompassed parts of Texas and the Gulf coast up to Mobile. Many times over these US citizens illegally settled in Spanish territory and by 1810 Baton Rouge was almost entirely English speaking with a substantial number of British Loyalists refugees from the American revolution still living there. Working in the shadows of this migration was a series of factions including a secret Freemason society called “the Order of the Lone Star.” Ultimately the topic of this Lone Star order will be subject for a later article but it was established in New York in 1790 for the “conquest of territory owned by Spain in the New World.” Beside this organization, Governor William Claiborne of Louisiana and Governor David Holmes of Mississippi, were working as President James Madison's two chief agents in securing intelligence on and planning the annexation of West Florida. These entities began sowing the seeds of rebellion and from June to September 1810, many secret meetings occurred in the Baton Rouge District, such as in the “Egypt Plantation” of Alexander Stirling. Out of those meetings grew the West Florida rebellion and the idea of the establishment of an independent Republic. Upon hearing of the rebellion, President Madison wanted to immediately mobilize troops to invade and occupy the district but failed to get congressional approval. However, this body of rebels, composed of mostly US settlers but also French and Germans, was not ready to wait around.

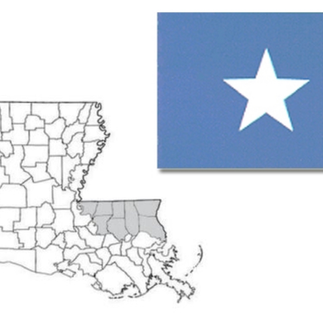

On 23 September 1810, over 50 armed rebels mobilized under the command of Kentucky Senator Philemon Thomas. It was taught erroneously for years that the local population rose in rebellion of Spanish rule but evidence does not support this claim. According to history professor Sam Hyde of Southeastern Louisiana University “Thomas’ army violently suppressed opponents of the revolt, leaving a bitter legacy in the Tangipahoa and Tchefuncte River regions.” Professor Hyde continues by explaining the revolt was largely supported by the Anglo populations of west Florida but not by the French or Hispanic areas: “Residents of the western Florida Parishes proved largely supportive of the revolt, . . . while the majority of the population in the eastern region of the Florida Parishes opposed the insurrection.” These armed US settlers stormed the local fort, Presidio San Carlos in Baton Rouge, carrying a solid blue flag bearing a single five pointed white star. The first Lone star flag ( this is the Texas connection and subject of a later article), which no doubt had its roots in the Order of the Lone Star. Presidio San Carlos was extremely undermanned, as were most of the Spanish forts along the Gulf Coast. The Spanish army was spread thin due to the Napoleonic wars and the various ongoing revolutions elsewhere. After a short but bloody firefight, the rebels took control of the Fort, killing 2 of the 4 Spanish soldiers stationed there. They also captured Don Carlos de Hault de Lassus, Commander of the Baton Rouge District since 1808. Don Lassus was actually a Frenchman who served the Spanish Army and in 1791 his family had fled the French Revolution to Spanish Louisiana. Don Lassus was imprisoned along with other Spanish officials and the rebels flew their Lone Star flag over the Fort and declared the Republic of the Lone Star. They claimed the entirety of the colony as the West Florida republic but most of the population of West Florida was against the insurgency and ignored the proclamation. The official boundaries secured by the rebels did not constitute even half of West Florida’s territory, consisting in only 8 prominently Anglo eastern counties of what is today Louisiana. Fortunately for the rebels, Spanish officials showed restraint not wanting to start a war with the United States on top of their other conflicts. However, these rebels were determined to spread their revolution and secure the entire West Florida.

Shortly after the rebellion, the rebels made plans to capture Mobile and Pensacola. Reuben Kemper, a Virginia native, raised a milita to undertake the operation. Kemper had previously been expelled for attempting to take another persons homestead by force in 1800 and in 1804 he failed in capturing Baton Rouge with a milita from Mississippi. The expeditionary force under Kemper was a small, hoping to recruit along the way and encourage the locals to rise in revolt but they failed to attract anyone. Kemper’s force was ultimately put down by the Spanish just outside of Mobile, and when Kemper crossed into the Mississippi Territory, US forces there arrested him, not wanting to provoke Spain. He was more fortunate than his colleagues, who were captured by the Spanish authorities and sent as prisoners to Havana, Cuba. As the weeks passed, the West Florida Republic became strife with disagreement between the factions that rose to give it power. Some settlers wanted the US to annex the territory, others wanted it to expand into a true nation, while French republicans wanted revolutionary France to regain control. St. Francisville, the town of discussion, was named as the capital of the West Florida Republic. What became of the Capuchins and their Monastery is unknown, as there is no surviving records of the event. We know that the monastery was eventually destroyed by fire but the details have been lost to time. What likely occurred is the Monastary was sacked like the other Spanish buildings and the friars were expelled among the other Spanish and Frenchmen in the region. According to Dr. Samuel Hyde of the Center for Southeast Louisiana Studies, the Spanish inhabitants had their homes and crops burnt, cattle killed, and many were murdered by the rebels, including one who was burned alive. Perhaps the fire that destroyed the monastery was related to the rebels activity. We only know for certain that Father Francis of Lennan, likely a capuchin priest, was arrested in St. Francisville and expelled from the republic. On 7 November 1810 Fulwar Skipwith was elected as “Governor” of the West Florida republic. Skipwith was originally appointed in 1795 George Washington to the staff of James Monroe as ambassador to France, and former consul general to France under President Thomas Jefferson. During Skipwith’s inaugural address he espoused manifest destiny by saying: “The genius of Washington, the immortal founder of the liberties of America, stimulates that return, and would frown upon our cause, should we attempt to change its course.” One of his first decisions was to direct militias to prepare to capture the remainder of West Florida from Spain. However this never came to be. On 9 December, the US army marched into the territories of the “West Florida Republic.” Governor Claiborne of Louisiana entered St. Francisville with an Army contingent of 300 Infantry from Fort Adams under the command of Colonel Leonard Covington and refused to recognize the West Florida government. In fact in October the US President Madison and congress had refused to recognize the west Florida republic. President Madison proclaimed that the Louisiana purchase had included all the territories that were "originally" part of French Louisiana, a word not found in neither the 1800 treaty nor the 1803 purchase. Nevertheless, the US army marched into St. Francisville and Baton Rouge, forcing Skipwith and his legislature to accept Madison's annexation proclamation. According to the French negotiator of the Louisiana Purchase, François Barbé-Marbois, "The Louisianans themselves agreed that the Baton Rouge district had been considered to belong to Florida, but, nevertheless, the state legislature declared, by one of its first acts that this district of country was a portion of Louisiana. ... but this eagerness to strengthen doubtful pretensions by possession, does not accord with the spirit of justice that characterizes the other political acts of the United States." Despite the proclamation, the remainder of West Florida was under Spanish control until the War of 1812, when the US army would capture Mobile, pushing the border of the US and Spain to the current Alabama-Florida lines. Spain did not agree to relinquish its title to any of the West Florida territory occupied by the United States until 1819, upon the signing of the Adams–Onís Treaty.

Now that we have answered our original questions regarding the name of St. Francisville and its original Church, we come back to our “Grace Episcopal Church” whose history officially starts with the West Florida republic. According to a history of the church written in the 1950s by the late Mabel Spinks Martin, this is said of the congregation: “It was these feisty Anglicans, many of whom had participated in the revolt against Spanish rule, who on March 15, 1827, formed an association to establish an Episcopal church in St. Francisville. At that time there was only one Episcopal church in Louisiana, Christ Church in New Orleans.” The history continues: “In 1828, the vestry purchased four lots for a church and entered a contract with Willis Thornton "to erect, build, and construct a Church of brick in good substantial manner.. The vestry passed a resolution that the cornerstone of the church be laid with "Masonic formalities." The church was first used through the winter of 1828-29, even though it was "not painted, plastered or ceiled.” During the Civil War the Grace Church was severely damaged by Union Artillery, who had been ordered to fire upon any structure they saw. Another notable fact during the war, is a moment called "The Day the War Stopped” by local historians. Union officer, Lt. Cmdr. John E. Hart of New York, committed suicide in Louisiana in a fit of delirium, perhaps brought on by yellow fever or perhaps by remorse. Lt. Cmdr. Hart had requested a Masonic burial, so a delegation was sent to one of Louisiana's oldest Masonic lodges, Feliciana Lodge No. 31, F&AM. The grand master of the lodge was serving in the Confederacy, but Grace Church's Senior Warden W.W. Leake "persuaded him to honor the request for Masonic burial … as a Mason it was his duty to accord Masonic burial to the remains of a brother Mason regardless of circumstances in the outside world.” Hart was buried in the Masonic lot in the cemetery at Grace Church with services conducted by the rector, the Rev. Daniel Lewis, "under a flag of truce.” In 1883, the restoration of Grace Church began and thus it has been to this day. Around a decade before, in 1871, the first Catholic Church since Spanish rule was built Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish. Before that Mass had been said in private residences by visiting priests. This Mount Carmel parish however, is not built not he grounds of the original St. Francis Monastary. So where was this Monasatry and what is left of it? Well there is no deffiative answer but according to historian Stanley Clisby Arthur, with the St. Francisville Democrat 1935: “About 1785, after Spain's banner succeeded the British ensign, Spanish Capuchins supplanted their French brethren of the cowl and crucifix, a grant of land was acquired from the Spanish king and a church and rectory erected, only to be destroyed by fire shortly thereafter. The grant fixes the church property on the lands now occupied by the cemetery of the Catholic church and also included the ground where the present Episcopal church now stands. One of the first priests stationed there was the Reverend Michael O'Reilly, educated for the priesthood in Spain, who came to Louisiana to administer religion in 1787.” So here we find a full circle, and one that almost perfectly tells the story of our Catholic Faith in the rest of Florida. Most of our history, our heritage, and our faith has been lost in the Freemason March against Christ the King and his Christendom. The little history that is widely embraced, sits in the shadow of the accomplishment of Protestants, Freemasons and the enemies of our God. While the local Freemason lodge in St. Francsville established in 1828 has nothing officially claiming its association with the West Florid rebellion, they fly the West Florida Lone star off their lodges balcony next to the Star-Spangled Banner. The Story of St. Franicville, Grace Church, and the first US incursion into Catholic Florida is more than a prelude of the upcoming articles but a synopsis of the entire experience.Most of our Catholic history is hidden or forgotten, if it is honored it is not as venerated as their history or considered a mere part rather than the foundational stone. After all history is not merely a study of the old but a study of His Story, the from the creation, fall, and redemption of man. Upon the ruins of this Capuchin Monasatry, he foundation of the city, sits the focus of historical attention, a Protestants Church blessed by Masons and established through the conquest of Catholic peoples.

Comments